The longest standing track and field record for the continent of Oceania is from 1968. Oceania is sometimes referred to as the Pacific Island continent. It is made up of 14 countries, 42 million people, and a diversity of cultures and religions. With all the advancements in nutrition, training methods, and human performance, it is surprising that a continental record has existed for more than 50 years. It is more surprising that the record is held in the 200m dash. The North American continental record in the 200m dash has been broken more than ten times since 1968. I don’t have a good explanation for why nobody from Oceania has run faster than 20.06 for 200m. I really only care about this little track and field factoid because of the man who holds the record, Peter Norman.

Allow me to switch gears for a paragraph or two…

For those of us who recognize and take seriously the historical and ongoing personal, social, and institutional racism that exists in America, the situation can be confounding. Let me be clear, well-meaning white people are in no way the victims amid this confusion. However, it can be hard to know what to do to try to correct a ‘wrong’ that is so wrong, it can never be righted. Hopefully, it doesn’t lead a person to despair, inaction, and simple hand-wringing. “People can cry much easier than they can change,” according to James Baldwin. Yet, I also know that taking control, and attempting to solve every problem reinstitutes patterns and forms of white domination that those who are fighting for racial justice are working to dismantle.

When should I lead? Who should I follow?

I know, and I have been told, that I need to do my own work. I also know, and have been told, I need to listen to those who know. I need to learn from the experiences of the historically and socially marginalized and put my body on the line for others.

Is there a better way than creating rules or applying an ethical framework to every situation? Perhaps, we might look to historical figures for examples and seek to imitate. I learn better this way. I hope it makes me a better ally and partner. It puts me in the world and asks questions of me. What are you going to do about this thing, right now? I am still trying to get a handle on what I am talking about, but it seems to be a form of ethical hagiography. Theologian Paul Griffiths writes, “Prohibitions [rules] produce a striving toward a standard; hagiographies write that standard on the flesh.” When we look to historical examples, we see justice enacted in time, materially. We seek to imitate those who have acted rightly, and we spend less time being confounded by theoretical ethical questions. This brings me back to Peter Norman.

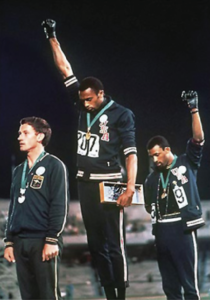

Norman died in 2006. John Carlos and Tommie Smith were both  pallbearers and eulogists at his funeral. If Carlos and Smith are unfamiliar names to you, you may know them better by the famous photo on the podium at the 1968 Olympic games in Mexico City. They gave the black power salute from the podium. Smith told the press that they demonstrated “for those individuals that were lynched, or killed and that no one said a prayer for, that were hung and tarred. It was for those thrown off the side of the boats in the Middle Passage.” Peter Norman is the silver medalist in the famous photo. The three men are being recognized as the three medalists in the 200-meter dash. Norman ran 20.06.

pallbearers and eulogists at his funeral. If Carlos and Smith are unfamiliar names to you, you may know them better by the famous photo on the podium at the 1968 Olympic games in Mexico City. They gave the black power salute from the podium. Smith told the press that they demonstrated “for those individuals that were lynched, or killed and that no one said a prayer for, that were hung and tarred. It was for those thrown off the side of the boats in the Middle Passage.” Peter Norman is the silver medalist in the famous photo. The three men are being recognized as the three medalists in the 200-meter dash. Norman ran 20.06.

Norman was a devout Christian who belonged to a Salvation Army family. He didn’t know Carlos or Smith very well before the 1968 Olympics. It was the beginning of a long and cherished friendship between the three men. Before Carlos and Smith told Norman what they were going to do, the three men talked about their faith. A faith in God they all shared. Carlos and Smith knew that they would face blowback for their demonstration, and they tried to warn Norman. The way Carlos tells the story is that they wanted to make sure he knew what he was getting himself into. They were walking a fine line between inviting Norman to participate and warning him of potential repercussions. In his book, Carlos recounts that he didn’t see any wavering from Norman, “all I saw was love.”

Smith and Carlos were instrumental in the founding of the Olympic Project for Human Rights. In 1968, several of the U.S. Olympians wore badges that designated them as part of the project. The goal of the projects was to protest the treatment of black people in America and South Africa. This was the early days of the OPHR, so it was mostly Americans who wore the badges. On the way up to the podium, Norman asked an American rower if he could have his OPHR badge and he obliged. Just before they received their medals Smith and Carlos asked Norman if he was sure he wanted to go through with the demonstration. Norman assured them, “I’ll stand with you.”

Smith and Carlos faced scrutiny for their role in the demonstration in the United States. Things weren’t much different for Norman in Australia. He became the consummate ally and example for those fighting for human rights and dignity in Australia. Which also meant that others thought he had shamed his country and that the Olympics were no place for such gestures. He was a public outcast, but he remained outspoken. The event inspired him to speak out about the treatment of Indigenous peoples throughout Oceania. His track career ended abruptly, but not because he had succumbed physically. He was deserving of a spot on the 1972 Olympic team, but he was left off. The hatred and vitriol he faced in his native Australia, mixed with a serious injury that required surgery drove him into a state of depression and alcoholism.

He relied on the friends he made in 1968 to help him. He had grown especially close to John Carlos. Carlos helped Norman through his struggles and showed him public support when Australia chose not to recognize him during the 2000 Sydney Olympics. A clear snub for a deserving athlete.

There were real stakes for Norman in 1968. He wasn’t the subject of a long history of systemic oppression and violence. He didn’t have to go through what Smith and Carlos went through. However, had he just walked the line he would have probably been remembered as a national hero in his native Australia. Norman’s story doesn’t give us an ethic or a program to live our lives by. His symbolic and material actions didn’t end racism. Yet, when he was asked to risk his own personal well-being, reputation, and security to stand for the justice and dignity of others, he acted. In the moment, he didn’t ask about a follow up strategy or what this demonstration would be accomplishing. Norman was asked to be an ally in the cause for racial justice and human rights. It seemed like a simple gesture. “I’ll stand with you.”